The Dropbox S1 was recently released and regardless of how you cut it, this is an incredible story. Founded in 2007, Dropbox has 500 million registered users – 11 million paying – and had $1.1 billion in revenue in 2017.

Perhaps the most impressive aspect of the story is that co-founders Drew Houston and Arash Ferdowsi together own 35 percent of the business. It’s great to see founders rewarded for their sweat equity. This is another big win and further proof of the consumerization of the enterprise industry.

Just as enterprise software shifted from on-premise to SaaS, we’re in the midst of another shift, though less pervasive, from enterprise sales & deployment (top-down) to consumerization sales & deployment (bottom-up). This excerpt from the S1 showcases this concept well:

Our 500 million registered users are our best sales people. They’ve spread Dropbox to their friends and brought us into their offices. Every year, millions of individual users sign up for Dropbox at work. Bottom-up adoption within organizations has been critical to our success as users increasingly choose their own tools at work. We generate over 90% of our revenue from self-serve channels— users who purchase a subscription through our app or website.

In 2017, over 40% of new Dropbox Business teams included a member who was previously a subscriber to one of our individual paid plans. We believe that a large majority of individual customers use Dropbox for work, which creates an opportunity to significantly increase conversion to Dropbox Business team offerings over time.

While a very different business from Dropbox, Wix, the cloud-based development platform, laid out a similar bottom-up go-to-market strategy in a recent annual report:

We could pay a substantially identical amount to acquire fewer registered users that generate premium subscriptions at a higher rate versus acquiring more registered users that generate premium subscriptions at a lower rate. The net amount of premium subscriptions would be the same, but in the former case we would have acquired fewer new registered users overall. We prefer the latter case due to the benefit of gaining more registered users and having a larger pipeline of registered users that can generate premium subscriptions over time based on the long “tail” of premium subscriptions that each cohort generates. This larger number of registered users also creates more overall users of our platform who can recommend others to our site. In addition, a single registered user can purchase multiple premium subscriptions. This fact, coupled with our preference to grow the size of our user base even if the rate of purchase of premium subscriptions is lower, is why we do not consider the rate at which registered users purchase a premium subscription (or any other measure of “conversion”) to be a meaningful measure of the success of our business.

In sum, the strategy is to optimize around the number of users in each cohort for two primary reasons: to increase your odds of acquiring a user who could become a whale down the road; and to assist word-of-mouth acquisition due to the sheer number of individuals who have tried your product.

This only works if you have a superior product, of course. Dropbox knows this and spent $380 million on R&D last year – 35 percent of revenue versus the industry average of 19.4 percent. Their primary competitor, Box, spent $102 million (28 percent of revenue) through the first nine months of 2017. Note too that Atlassian, the company that wrote the “R&D to replace S&M” playbook, spent $310 million last year on R&D, or 50 percent of revenue.

A stellar product is always behind efficient S&M spend – this is exactly the case for Dropbox. For the last seven quarters ending Q4 2017 Dropbox’s magic numbers (a SaaS metric used to determine sales efficiency) are: 0.9, 1.4, 1.2, 0.6, 1.1, 1.2, and 1.0.

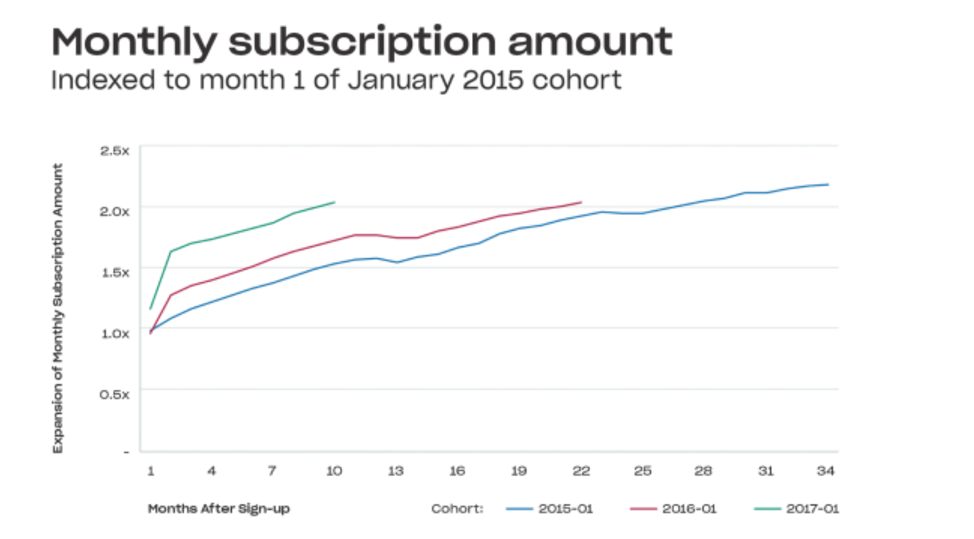

The next question becomes: how do these users perform once they’ve signed up? Dropbox provided January cohort performance for the last three years, which shows improving performance by cohort:

Source: Dropbox, Inc. S-1 Registration Statement, February 23, 2018.

These amounts increase as more registered users in each cohort convert to paying users, paying users upgrade to premium subscription offerings, and team administrators purchase additional licenses. These amounts decrease when paying users terminate their subscriptions, downgrade their subscriptions to a lower tier, or team administrators reduce the number of licenses on their subscription plans.

This cohort performance speaks exactly to the strategy laid out in the Wix filing: “We prefer the latter case due to the benefit of gaining more registered users and having a larger pipeline of registered users that can generate premium subscriptions over time based on the long ‘tail’ of premium subscriptions that each cohort generates.”

The key driver of this net-negative revenue churn for Dropbox is the non-paying customer base that signed up in each cohort. The question all investors should have here is: what does customer concentration look like in each cohort? Is their average-sized growth across a large number of customers accounting for the cohort revenue growth, or is it that they’re capturing a small number of whales in each cohort that expands exponentially? We don’t have this data from the filing, but if it’s the latter that’s obviously much less appealing as these big customers risk disrupting the health of the entire cohort with churn or down-sell, which happens more frequently when very large customers know they have pricing power.

Dropbox offered one additional view of revenue retention: “As of December 31, 2017, our blended Annualized Net Revenue Retention across the entire business, including individuals and Dropbox Business customers, was over 90 percent.” This stat has the potential to be concerning over time. Unlike the cohort retention above, this only considers customers that were paying out of the gate, not non-paying registered users. “Annualized Net Revenue Retention is the percentage of annualized revenue retained over a 365-day period, inclusive of changes in price, changes in number of licenses, upgrades and downgrades to different subscription plans, and churn”. We do not know what gross churn is, but, generally we’d like to see the net number over 100 percent. A high-gross churn number defines a leaky bucket and can put pressure on both S&M (less efficient due to churn) and R&D (less efficient due to the need to innovate to retain users) over time.

It’s unclear if churn is a problem today, but all problems are of the high-quality type when you’re coming off of a $1.1 billion revenue year with healthy growth and 500 million users across 180 plus countries. Congrats to the Dropbox team on an incredible journey.