We invested in a company called Skybox Imaging in 2012. The founders of Skybox had an audacious plan — to radically change the way satellite imaging was done. Before Skybox, high resolution images of the earth from space were something that really only one customer could afford — the US government. There were only a handful of companies who had the technical chops and the capital to build spy satellites, and these satellites were the size of small dumpsters. They were launched on large, expensive rockets and took up most of the cargo space. Because of these constraints, only a handful of these high resolution satellites were launched, and commercial (non-government) buyers couldn’t get reasonably priced images, and worse, they couldn’t get timely images when they needed them. To make things worse, the data that came out of these satellites was large and inaccessible to average users — specialists were needed to manipulate and interpret the images.

Along came Skybox with a different approach — they would build small satellites that could provide images with very high resolution, but because these satellites would be the size of a college-dorm refrigerator, they would be cheap to build — less than 5% of the cost of a large spy satellite. And because they were small, they would be cheap to launch. They could ride-share with big satellites at low cost, or go as a group of 5 or 6 small satellites in a single rocket launch. The analogy was that of the mainframe computer shrinking to the size of a desktop computer with all the similar advantages of a revolution in cost and capability. And the data would be stored in the cloud, using popular open source technologies and would be accessible through the Internet. Suddenly new applications opened up in agriculture, weather, climate studies, security and border control, fisheries, and tens of other industries.

Fast forward to today — Google acquired Skybox in 2014 for $500m and now there are 7 Skybox satellites in space, with 5 more scheduled to launch in the next few months.

But the story of miniaturization in space continues. A few years ago the Cubesat movement was launched, and now satellites have dropped to a form factor made up of building blocks as small as 10cm cubed. It was as important a change as the desktop computer shrinking to the size of a laptop. Because Cubesats were cheap to build and launch, some of their disadvantages such as lower resolution imaging could be overlooked in favor of frequency of revisit and coverage of new areas.

But even with all the advances in satellite imaging a couple of inconvenient truths remained — the earth is frequently covered in clouds, and about half the earth is in darkness at any given time. Today’s satellites can’t get images in those conditions. Technologies exist to get around that, in particular something called Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR), but again this was limited to big, inaccessible, expensive satellites operated mostly by governments.

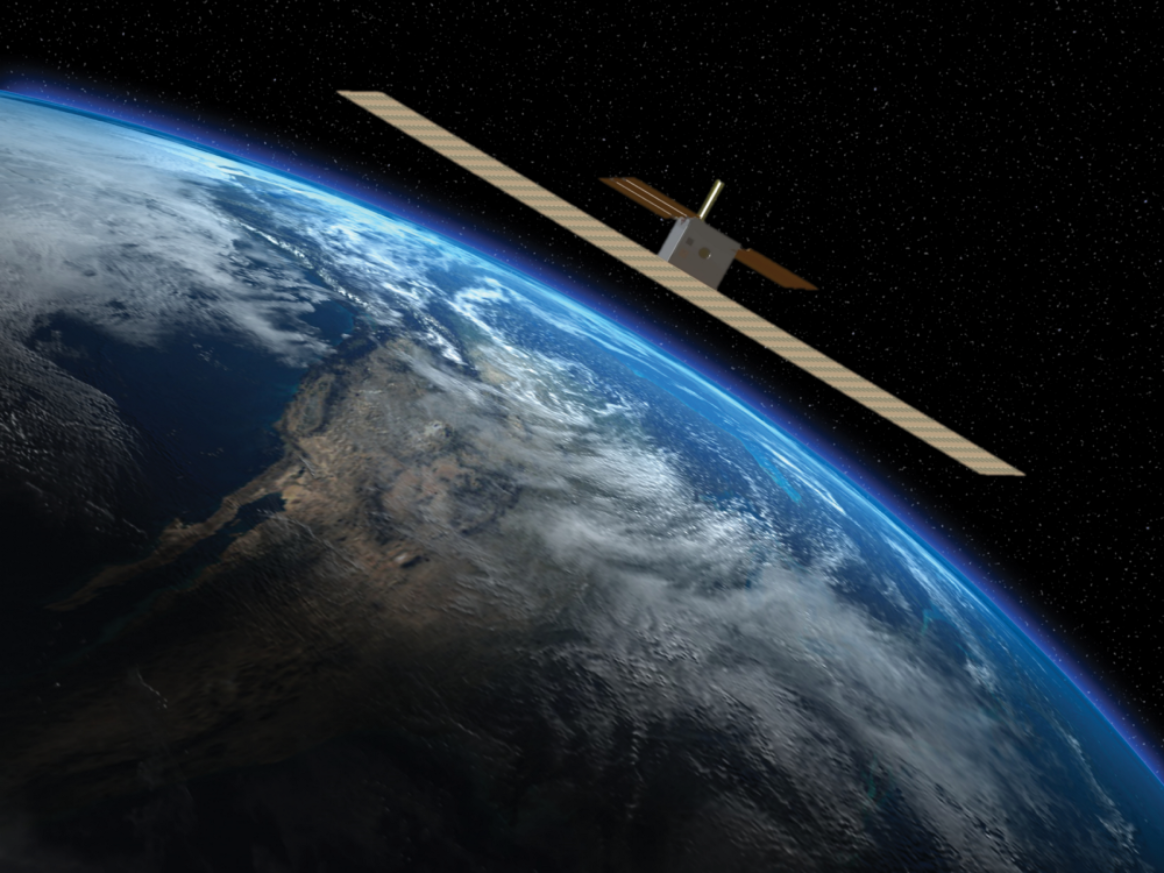

Enter Capella Space. Their audacious idea was to harness SAR technology and fit it into a cubesat. Since the antennas and solar panels required to operate SAR are huge in size, it takes a bit of tech magic to fit them in a cubesat form factor. The challenge is large but so are the rewards. The market size of readily available radar images is estimated to be in the billions, and new rocket launch vehicles are being funded (by firms like Canaan) to provide more frequent launches for cubesats.

Capella plans to launch their first satellite at the end of 2017.